Chapter 3: The context of the plays

Recommended reading

Braunmuller, A.R. and M. Hattaway (eds) The Cambridge Companion to English Renaissance Drama. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003) [ISBN 9780521527996].

Chambers, E.K. The Elizabethan Stage. Four volumes. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1923) [out of print]. Still the definitive work on factual matters concerning the people and practices of Elizabethan theatre.

Clare, J. Art Made Tongue-tied By Authority. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990) [ISBN 9780719024344]. Recent work on state censorship of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama.

Cox, J.D. and S. Kastan (eds) A New History of Early English Drama.(New York: Columbia University Press, 1983) [ISBN 9780231102438].

Dutton, R. Mastering the Revels: The Regulation and Censorship of English Renaissance Drama. (London: Macmillan, 1991) [ISBN 9780333453711].

Gurr, A. Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004) [ISBN 9780521543224]. Contains just about everything known about the contemporary theatrical audience.

Gurr, A. The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009) [ISBN 9780521509817]. The best single introduction to the material conditions of the theatre.

Mullaney, S. The Place of the Stage: License, Play, and Power in Renaissance England. (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1995)[ISBN 9780472083466].

Nagler, A.M. Shakespeare’s Stage. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981)[ISBN 9780300026894]. Makes a very strong case for the use of curtained booths (instead of a back-wall alcove) and perspective scenery (rather than bare boards) on the public stage and demonstrates the wide-reaching implications of this conclusion.

The rise of the theatres

Prior to the sixteenth century, no purpose-built theatres existed in England. The period of Shakespeare and Jonson witnessed remarkable developments for English drama, in terms of writing, staging, and the organisation and professionalisation of the theatrical companies.

The most successful theatres of the day were located in the London borough of Southwark, in Bankside, on the south bank of the Thames, an area known for the variety of seditious and morally suspect entertainment on offer there. Theatres such as the Globe, Shakespeare’s theatre, built in 1599, and the Rose, built in 1587, plied their trade in the neighbourhood alongside brothels, inns and bear-baiting pits, where customers paid to see a bear fight with dogs. Given the raucous and unseemly nature of the Bankside area, it seems unlikely that going to a play was quite the rarefied and genteel pursuit it is today. Given the type of person frequenting the area, and the types of entertainment they were after, the early-modern theatre must have been a very exciting, lively and combative place, just in order to attract an audience.

The playhouses of Bankside were located in Southwark due to the hostility theatrical performances attracted from the City of London authorities who held jurisdiction of the financial district of London on the north side of the river. The City of London was largely under Puritan control, and as such, public theatrical performances were forbidden within the confines of the City walls. Puritans were a particularly strict, sober and disapproving sect of Protestants who believed strongly in hard work and avoiding all temptations into sin. As such, they are often considered to be the antithesis to the flamboyant and artistic players, who had been considered no better than vagabonds until only recently. The tension between Puritans and theatre practitioners often manifests itself in the plays, with Puritan characters often becoming the targets of harsh satire in comedy.

Activity

Try and find some examples of Puritan characters. How are they represented, and what does their treatment tell us about dramatists’ attitudes towards them?

Early-modern stages and staging

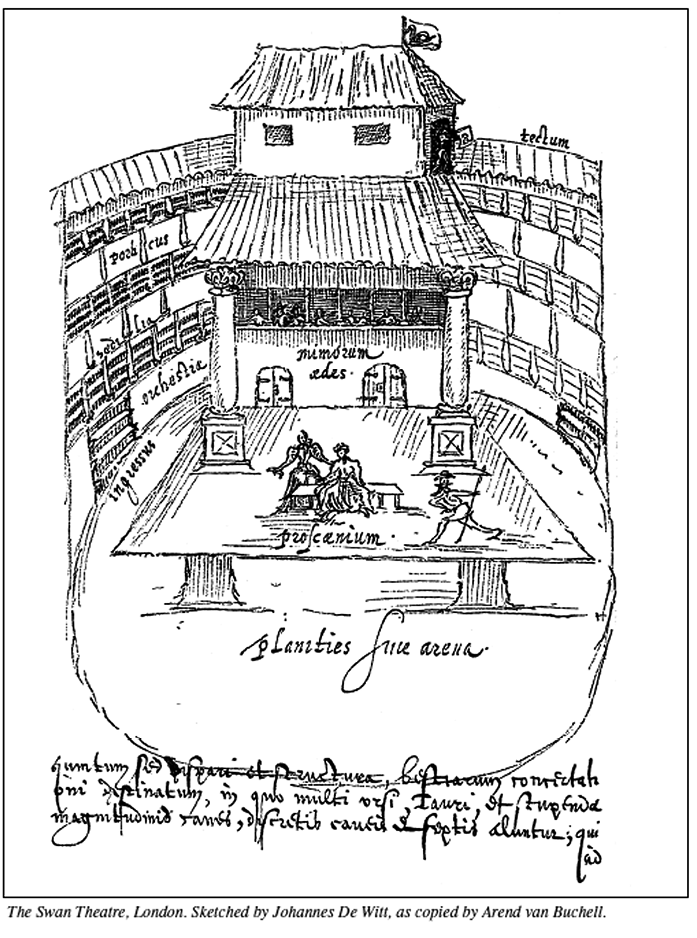

This drawing shows the layout of the Swan Theatre, as it was seen by a sixteenth-century Swiss tourist to London. Although we cannot be entirely sure how accurate a representation it is, scholarly research and archaeological findings suggest that the De Witt sketch is probably typical of the kind of early-modern stages that would have been found on Bankside. The Elizabethan public playhouses were not designed completely from scratch, but rather represent a bringing together of the assorted types of playing space that actors would have been used to performing in before they had permanent homes. As a result, the wooden-board stage that thrusts into the audience, called a ‘thrust’ or ‘pinafore’ stage, is a direct descendent of the temporary booth stages that would be erected for one-off performances by touring companies. Similarly, the tiring house, the structure at the back of the stage where the actors would change and make their entrances and exits, sports two doors that mimic those of the great halls of the country houses of the aristocracy, who regularly invited players into their homes at times of celebration. The seating galleries that line the outer perimeter of the auditorium are themselves reminiscent of the galleries that lined the walls of the courtyards of coaching inns, another popular venue for one-off performances.

The arrangement of the theatre has repercussions for the perception of any play performed there. Rather than facing out into an auditorium that looks at it straight on, the early-modern stage was surrounded by galleries and standing spaces on three sides. This meant that the audience were offered a multiplicity of viewpoints on the stage at any one time, and a spectator in one of the galleries would get a perspective of the stage-action which would be very different from the perspective from another gallery. Immediately in front of the stage at ground level is a space for audience members to stand, known as the ‘pit’, which offers another perspective again.

Most stages built in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries use a design known as the ‘proscenium arch’, an arch at the front of the stage that frames the action almost as a border frames a postcard. It can be argued that there is an enormous difference between the dramatic experience one has viewing the Elizabethan thrust stage and the ‘proscenium arch’ stage, because the latter offers only a single perspective on the drama. Similarly, modern auditoriums require audience members to sit still and silently in the dark. With no artificial lighting available, and performances taking place in the afternoon, to often highly vocal crowds, the whole perception of attending the playhouse, and indeed what kind of cultural artefact a play might be, are different from the present day.

Some of the effects of the stage layout can be easily shown. The common occurrence of a line such as ‘Here comes my Lord of Norfolk, looking like a great big85’ is due to the great distance between the doors at the back of the stage where a character would enter, and the position at the front of the stage where they would be about to join a group. Such lines of dialogue fill the time during which the actor must make his way towards the others. Similarly, the absence of any means of showing where action takes place, as the early-modern stage used little or no scenery, and certainly not ‘realistically’ painted backdrops, gives rise to the frequent practice of the opening lines of a scene containing dialogue emphatically telling the audience where the scene takes place.

Activity

Staging is important for a study of comedy, due to the amount of quick movement, changes and entrances and exits required. Pick one or two scenes from Shakespeare and Jonson and think about how you might perform them on an early-modern stage.

The audience

It is impossible to reconstruct the exact social composition of the people who attended performances at the public playhouses, but the relatively low cost of entry, and the many references throughout the canon of Renaissance drama to the ‘groundlings’, lower-class denizens of the pit, and the existence of more comfortable galleried seats and ‘lord’s rooms’, all suggest that a wide cross-section of society may well have been in attendance. Given that the design of the theatre allowed for the occupancy of those with different levels of income and comfort needs, it seems likely that people of all social strata would have watched a play together. This is also reflected in the tone and structure of many Renaissance plays, which continually mix action with coarse and bawdy humour and sexual language, with beautiful rhetorical speeches and allusions to classical authors and gods. It has to be understood that the world of Renaissance drama was also a world of highly competitive business, and so it was imperative to maximise the appeal of drama, and not to alienate any members of the audience, in order to maintain profits.

Activity

Read the induction to Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair. What does it tell you about perceptions of authors, audiences and playgoing in the early-modern period?

Patronage and censorship

As previously mentioned, the City of London authorities were extremely hostile to drama. However, the court and courtiers supported it because they wanted to see plays performed in their houses, and their patronage of companies meant that they could have a troupe of players at their command whenever they wanted to entertain a guest or improve their standing at court with some magnificent display of hospitality. As a result, a great deal of tension existed between the City, the players and their patrons. The City was effectively run by the Lord Mayor and the Aldermen, who were elected by business interests. By way of countermeasure, the court exercised control of the players both through the patronage system and by enforced censorship of plays, as a means of calming the fears of those in the City who wanted drama very strictly and directly policed. It could be argued, therefore, that the theatres were something of a pawn in the struggles between the Court and the City.

Puritan businessmen found the theatres worrying for several reasons. One was that theatre involved many citizens gathering together at one place, which might give rise to problems in public order. Another was the ‘immoral teaching’ or subversive ideas that plays might contain. Yet the greatest fear was probably reserved for the fact that acting involved transgressions and disruptions of both gender and class, where men dressed up as women and commoners dressed as kings and queens. When it occurred off-stage, any challenge to the class system was considered to be extremely dangerous. Indeed, such transgressions were expressively forbidden by law anywhere except on the stage. Another objection frequently voiced was that the large congregations of people were aiding the spread of plague. This last objection, true as it was, also became a useful ‘cover’ for measures of social control that were really taken for other reasons.

Activity

What kinds of ‘transgression’ may be said to be dramatised in the plays? Try and find examples that may have been considered dangerous or outrageous by the Puritan authorities.

The censoring of plays was the responsibility of the Master of the Revels, who came under the authority of the Lord Chamberlain. A theatrical company would present the proposed script for a play, called the ‘Book’, to the Master of the Revels, who would either give an unconditional licence, a conditional licence or no licence at all. The first was complete approval for the play to go ahead without alterations. The second was an approval subject to certain alterations, such as the excision of particular lines, which the Master of the Revels would mark in the book. The last was a complete refusal, which generally meant that the project would have to be completely abandoned; this would only happen if the theatrical company had very badly misjudged the acceptability of the work they had commissioned from the dramatist.

The single most significant piece of state censorship was the Act of Parliament of 1606 entitled ‘Acte to restraine Abuses of Players’. This act outlawed the use of the name of God in oaths in plays (e.g. ‘By Christ I’ll do it!’) and affected not only new plays but revivals of old ones. This law is the reason that there is much greater use of pagan gods’ names in oaths (e.g. ‘By Jove’, ‘By Jupiter’) in plays written after 1606. If you wish to trace the influence of censorship on the plays of the period you will find Janet Clare’s Art Made Tongue-tied by Authority and Richard Dutton’s Mastering the Revels useful.

Personal satire against identifiable famous persons was just the kind of material a theatrical company could expect to have censored by the Master of the Revels. In 1601 the Privy Council warned the players at the Curtain theatre not to ‘represent upon the stage… gentlemen of good desert and quality that are yet alive under obscure manner’ as they had been known to do.

Activity

A complaint was made that Eastward Ho! satirised King James, and the dramatists were sent to jail for it. Try to find the offending material and judge how offensive it might be.

If the Master of the Revels missed it, the friends of the person satirised could be expected to complain about the play and have the offending production stopped until the offence was removed. Similarly, anything that appeared to engage with contemporary political issues would be potentially dangerous. One possible way to avoid the accusation of political subversion was to set the play in another country. The only plays Shakespeare sets in England are his English history plays; all the others, with the single exception of The Merry Wives of Windsor, are set overseas. Jonson, by contrast, sets most of his plays in London. One of the questions you should be able to approach by the end of this subject is an analysis of the degree to which setting serves to deflect accusations of subversion.

Learning outcomes

Having read this chapter, in conjunction with your own study, you should be able to:

- • describe the relationship between playwrights and Puritans in the sixteenth century

- • explain the concerns Puritans had about plays

- • sketch a diagram of a typical early-modern theatre

- • describe the origins of different aspects of these theatres, such as the ‘thrust’ stage

- • compare the early-modern to the proscenium arch stage and explain how each would have affected the staging of plays

- • describe the system of patronage that operated in Shakespeare’s and Jonson’s time

- • explain the role of the Master of the Revels.